Home » Articles posted by Wendy Jones (Page 6)

Author Archives: Wendy Jones

Technetium 99 studies and Breastfeeding

Earlier this year I had the pleasure of working with Rachel Bidder and others at Swansea Bay University Health Board on compiling information on Having a Tc‑99m Diagnostic Study whilst breastfeeding. Subsequently the information was shared in a presentation to the BNMS conference. In addition, the local team amended their information on MRI and CT to be more breastfeeding friendly.

The information from the Swansea team is reproduced here with their permission. If you have questions regarding expressing and storing, please contact your local breastfeeding team. My thanks to Rachel for allowing me to share this

Introduction

The vast majority of the radioactivity will be excreted via urine; however, a small amount will be excreted in breast milk. There are some precautions to follow to minimise the radiation dose babies receive. Radioactivity decays over time, meaning that not only will your body excrete it but the radioactivity itself will reduce. For Tc-99m, the radioactivity reduces by half every 6 hours, called the half-life. By following the advice in this leaflet (based on the ARSAC Notes for Guidance, 2022 and Drugs and Lactation Database, 2006), the radiation dose to your child from breastfeeding should be less than half of the annual natural background dose.

The disruption to your breastfeeding depends on the type of diagnostic study you are having. The interruption times given in this leaflet do not apply during the period of early lactation when colostrum is being secreted.

Before Your Appointment

All patients should ‘bank’ at least one feed before their appointment. Do this by expressing milk and storing it appropriately. Check the required breastfeeding interruption time for your scan using the table . It is recommended that you bank enough milk to feed your child over the length of this interruption period. If this is not possible for you then consider an alternative method for feeding your baby over this interruption period, such as using formula. Just before your appointment, you should feed your baby naturally.

After Your Appointment

You should not resume breastfeeding until after the total required period of interruption, as given for your study type in the table on the back of this leaflet. During this period of interruption, you should regularly express milk as fully as possible. This milk should not be used at this point. You can feed your baby during this time using a previously ‘banked’ feed. All milk expressed during the interruption time should either be discarded or stored in the freezer for at least 60 hours after your appointment. After 60 hours (10 half-lives), the radiation will have decayed to a safe level, and the stored milk can be used to feed (there is a small risk with this) or to bathe your baby as you please.

Once the interruption period has passed, you can continue to breastfeed your baby as normal.

Breastfeeding can be undertaken following subsequent pregnancies. Even if you have difficulty

expressing milk, the radioactivity will decay over time and will not be ‘stuck’ in your milk.

Summary

Reference

Notes for guidance on the clinical administration of radiopharmaceuticals and use of sealed

radioactive sources. Administration of Radioactive Substances Advisory Committee. Feb 2023

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1137032/guidance-clinical-administration-of-radiopharmaceuticals-and-use-of-sealed-radioactive-sources-2023.pdf

“The patient should interrupt breastfeeding for a period of time to ensure that the effective dose received by the infant is less than 1mSv”

To tell a mother with a neonate not to breastfeed for a period of time risks her developing mastitis and will undoubtedly have an impact on her ability in the future to breastfeed

Healthcare professionals have a duty to protect the breastfeeding relationship to support the health of the patient and the breastfeeding infant

See also:

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/

Hale TW Medications and Mothers Milk Online access

Ectopic Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

Sadly our family has experienced the tragedy of an ectopic pregnancy and the loss of a very brief dream. This has made me much more aware of the incidence and risk of this condition over. So some more facts – as my friend commented today I hate to waste any opportunity to educate!

I have also heard from several mothers who have been diagnosed with an ectopic pregnancy. They have variously been told that they cant breastfeed again for 2 months and 3 months. One distraught mother planned to pump and dump her milk for 3 months with the hope that she could return to breastfeeding later.

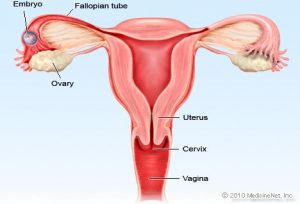

Ectopic pregnancy is a common, occasionally life-threatening condition, that affects 1 in 80 pregnancies. An ectopic pregnancy is when a fertilised egg implants itself outside of the womb, usually in one of the fallopian tubes. Symptoms usually develop between the 4th and 12th weeks of pregnancy. Women with an ectopic pregnancy may still be breastfeeding and wish to continue which can be supported.

Symptoms

- Ongoing bleeding that is sometimes red or brown/black and watery (like “prune juice”) should be investigated. The bleeding may be heavier or lighter than usual, but pregnancy test is still positive

- One-sided pain in your tummy which may be persistent or intermittent or a generalised discomfort with bloating and a feeling of fullness (not associated with eating) when lying down.

- Shoulder tip pain which is often described as pain unlike any you have ever experienced before. (Ectopic Pregnancy Trust)

Investigations

Your GP will refer you urgently to the early pregnancy unit at your local hospital. You may have your Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (HCG levels) measured over a period of several days. If you are having a normal pregnancy these should double approximately every 48 hours. A smaller increase can indicate a risk of of this being an ectopic pregnancy but this will be confirmed with ultrasound scans, initially across your tummy. It is likely that a transvaginal (internal) ultrasound scan will be required where a specialised probe is placed into the vagina to get a more detailed look at the reproductive organs.

Unfortunately, if it is confirmed over a period that you have an ectopic pregnancy it is not possible to save the pregnancy and it must be removed either by surgery or the use of methotrexate. The cells have not been able to be nourished and can never develop into the baby you thought you were expecting which can be hard to deal with.

Rupture of ectopic pregnancy

In a few cases, an ectopic pregnancy can grow large enough to split open the fallopian tube. This is known as a rupture which can be very serious, and surgery needs to be carried out as soon as possible.

Signs of a rupture include a combination of:

- a sharp, sudden and intense pain in your tummy

- feeling very dizzy or fainting

- feeling sick

- looking very pale (NHS Choices)

Methotrexate and breastfeeding

Mothers who are currently breastfeeding an older child can continue 24 hours after the methotrexate is administered.

“It is apparent that the concentration of methotrexate in human milk is minimal, although due to the toxicity of this agent and the unknown effects on rapidly developing neonatal gastrointestinal cells, it is probably wise to pump and discard the mother’s milk for a minimum of 24 hours post dose if given as a single dose (e.g. 50 mg/m2 IM for ectopic pregnancy).

The period in which the mother discards her milk may require extending (consider 4 days of interruption) if the dose used is quite high (>75mg). (Hale 2023). This is due to lack of data from research on accumulation in infant tissues rather than levels in breastmilk.

In a case report of a woman receiving 92 mg IM daily for 3 days (Baker T, Datta P, Rewers-Felkins K, Hale TW. High-dose methotrexate treatment in a breastfeeding mother with placenta accreta: a case report. Breastfeed Med. 2018 Jul/Aug;13(6):450-452 ), milk levels were collected and assayed for methotrexate although she was advised not to breastfeed.dose. Both methotrexate and its metabolite 7-hydroxymethotrexate levels in milk were exceedingly low. On day 2 of therapy, the average milk concentration of methotrexate was 8.6 ng/mL. The maximum concentration of methotrexate occurred at 2 hours and was found to be 16.9 ng/mL. The levels gradually receded and were 4.9 ng/mL at 24 hours. The relative infant dose of methotrexate (RID) was calculated at 0.11%. The half life of methotrexate is quoted as 8-15 hours (Hale 2023).

Infant Monitoring: Should patient resume breastfeeding more than 24 hours after the last dose of maternal therapy, monitor the infant for vomiting, diarrhoea, blood in the vomit, stool or urine. Lab work could be drawn if clinical signs of liver or renal dysfunction, anaemia, thrombocytopenia or an inability to fight infection.

Lactmed reports a study of one mother who was given a single intramuscular dose of 65 mg (50 mg/square meter) of methotrexate for ectopic pregnancy. Six milk samples were obtained from 1 to 24 hours after the dose. Methotrexate was undetectable (<22.7 mcg/L) in all milk samples (Tanaka 2009). In some 20% of cases more than one cycle of methotrexate is required to expel the products of conception. For each cycle breastfeeding should be avoided for 24 hours.

Hale quotes a milk plasma ratio of > 0.08 and relative infant dose of 0.13% – 0.95%. Peak serum concentrations appear 30-60 minutes after intra muscular dose (Jones 2018). Pharmacokinetic data is very variable as there in considerable inter individual variation (Martindale 2017).

Methotrexate and breastfeeding

There is not much information about methotrexate and breastfeeding, but it shows that methotrexate passes into breast milk in tiny amounts. Your doctor or specialist will advise what’s best for you and your baby.

If your weekly dose of methotrexate is 25mg or less, it may be possible to breastfeed. However, you must not breastfeed for 24 hours after taking your medicine. Your midwife or health visitor can give you advice about how to feed your baby while you wait 24 hours. https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/methotrexate/pregnancy-breastfeeding-and-fertility-while-taking-methotrexate/

For more information on methotrexate administration, side effects and monitoring see www.ectopic.org.uk/patients/treatment/

Ectopic pregnancy and breastfeeding fact sheet

Breastfeeding after surgery

After surgery breastfeeding can continue as normal as soon as you are awake and alert. If your nursling is unable to stay in hospital with you, you may need to express to avoid engorgement/blocked duct and to maintain your supply. Your expressed milk can be given to your baby at home. There is no need to pump and dump.

Vaccinations and Breastfeeding

Taken from Breastfeeding and Chronic Medical Conditions available from Amazon.

Most vaccinations can be undertaken during breastfeeding as they do not pass into breastmilk. For detailed information please check the Green Book which has sections for breastfeeding. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/immunisation-against-infectious-disease-the-green-book

- Chicken pox (varicella): compatible with normal breastfeeding

- Hepatitis A: compatible with normal breastfeeding

- Hepatitis B: Vaccinations are routinely offered to healthcare professionals who may come into contact with body fluids. Compatible with normal breastfeeding

- Influenza: compatible with normal breastfeeding

- Meningococcal C: Immunization of pregnant or lactating women with meningococcal vaccine increased the specific secretory IgA content of milk. compatible with normal breastfeeding

- MMR Injections: A breastfeeding mother can have an MMR injection if she is not rubella immune. Although live vaccines multiply within the mother’s body, the majority have not been demonstrated to be excreted in human milk (Bohlke K, Galil K, Jackson LA, et al. Postpartum varicella vaccination: is the vaccine virus excreted in breast milk? Obstet Gynecol 2003; 102:970–7). Although rubella vaccine virus might be excreted in human milk, the virus usually does not infect the infant. If infection does occur, it is well-tolerated because the virus is attenuated. Inactivated, recombinant, subunit, polysaccharide, conjugate vaccines, and toxoids pose no risk for mothers who are breast feeding or for their infants.

- Pneumonia: compatible with normal breastfeeding

- Polio: The injectable polio vaccine is inactivated and poses no risk when given to mothers who are breastfeeding. The oral vaccine may reduce the production of antibodies by the infant and immunisation of the mother before the infant reaches 6 weeks of age is not recommended.

- Tetanus Vaccination: One study of previously vaccinated infants found that at 21 to 40 months of age breastfed infants had higher IgG levels against diphtheria, higher secretory IgA levels in saliva against diphtheria and tetanus and higher faecal IgM against tetanus than formula-fed infants. There is no contra indication to a breastfeeding mother having this vaccination.

- Tuberculin and BCG: There is no reason to avoid tuberculin testing during breastfeeding nor to avoid use of the BCG vaccine unless the mother is immunocompromised.

- Typhoid Vaccination: One study of previously vaccinated infants found that at 21 to 40 months of age breastfed infants had higher IgG levels against diphtheria, higher secretory IgA levels in saliva against diphtheria and tetanus and higher faecal IgM against tetanus than formula-fed infants. There is no contra indication to having the vaccination and continuing to breastfeed.

- Whooping Cough: there is no evidence of risk of vaccinating breastfeeding mothers with the whooping cough (pertussis) vaccine as part of the campaign to protect new-born babies.

See also SPS Giving vaccines and breastfeeding

https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/giving-vaccines-during-breastfeeding/

Smoking cessation and breastfeeding

A while ago, in my previous working life I was a smoking cessation counsellor. I’m sure that there are many who tried to quit as a New Year’s Resolution or are considering a pregnancy and want to quit now or who now find themselves pregnant . I reworked a presentation I gave in Blackpool a few years ago so that it is aimed at women but could also help those helping mothers to quit smoking. Let me know if I can help wendy@breastfeeding-and-medication.co.uk

See also the impact of paternal smoking on breastfeeding https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2023/40/the-impact-of-paternal-smoking-on-breastfeeding

Accidentally taking one dose of aspirin when breastfeeding

It is surprising how often mums manage to take products containing aspirin by mistake – they are given by well meaning partners, friends at the office or just taken quickly for pain. Then the realisation that aspirin is contra indicated in breastfeeding. What to do? How long to express?

The answer is actually simple with one single accidental exposure. The risk is low and I have been unable to find any references associating Reye’s syndrome with the amount of aspirin passing through breastmilk.

Reye’s syndrome This is a rare syndrome, characterised by acute encephalopathy and fatty degeneration of the liver, usually after a viral illness or chickenpox. The incidence is falling but sporadic cases are still reported. It was often associated with the use of aspirin during the prodromal illness. Few cases occur in white children under 1 year although it is more common in black infants in this age group. Many children retrospectively examined show an underlying inborn error of metabolism.

accidental/one off dose of aspirin factsheet

Aspirin is not generally recommended to be used by lactating women due to the link between aspirin and Reye’s syndrome. Aspirin is 80–90% bound to plasma proteins. Erickson and Oppenheim (1979) found that even at a dose of 4 g per day the levels of salicylate measured in one mother suffering from rheumatoid arthritis were below the level of detection. Findlay et al. (1981) studied two mothers exposed to 454 mg aspirin. They found that salicylic acid penetrated poorly into milk, with peak levels of only 1.12–1.60 µg per millilitre, and estimated that about 0.1% of the mothers’ total dose would appear in breastmilk.

Accidental consumption of a single dose of aspirin by a lactating mother need not lead to expressing and discarding of her breastmilk. Theoretical infant dose through breastmilk is quoted as 0.25 mg per kilogramme per day with a relative infant dose quoted as 2.5–10.8% (Hale 2017 online access).

The BNF states: ‘Avoid – possible risk of Reye’s syndrome; regular use of high doses could impair platelet function and produce hypoprothrombinaemia in infant if neonatal vitamin K stores low’. Vitamin K is secreted in breastmilk and is added to formula.

If taken accidentally no evidence that continuing to breastfeed after single dose is harmful.

References

Erickson SH, Oppenheim GL, Aspirin in breastmilk, J Fam Pract, 1979;8(1):189–90.

Findlay JW, DeAngelis RL, Kearney MF, Welch RM, Findlay J, Analgesic drugs in breastmilk and plasma, Clin Pharmacol Ther, 1981;29:625–33.

Glasgow JF, Reye’s syndrome: the case for a causal link with aspirin, Drug Saf, 2006;29(12): 1111–21.

Leave a comment

Logged in as Wendy Jones. Log out?

Comment

Follow us

Type 1 diabetes and breastfeeding

Information taken from Breastfeeding and Chronic Medical Conditions available from Amazon

“in the early stages when getting used to feeding I found I had to keep snacks handy to avoid having hypos but apart from that everything went well. I had to be determined due to the added energy being used and the normal fatigue I get but having hoped to get to 6 weeks we’re now 24 months and still feeding.”

Description

Type 1 diabetes usually first develops in children or young adults. In the UK about 1 in 300 people develop type 1 diabetes at some stage. Itusually develops quite quickly, over days or weeks. Type 1 diabetes is an auto-immune disease caused by the destruction of the insulin producing beta cells in the pancreas. There is a genetic component in the development, but it is triggered by environmental factors such as early introduction of cow’s milk protein, viral infections, and exposure to toxins.

Symptoms of type 1 diabetes are excessive thirst, frequent passing of urine, extreme tiredness, and dramatic weight loss. Untreated or poorly controlled diabetes leads to damage to the eyes, feet, nerves, kidneys, and increased risk of coronary heart disease. With treatment and monitoring these effects can be minimised.

If insulin levels are unstable in pregnancy the baby may be born large for dates. Miscarriage, pre‑eclampsia and preterm labour are more common in women with pre‑existing diabetes. Folic acid supplements 5mg a day should be taken before conception and for the first 3 months of pregnancy.

Mothers with Type 1 diabetes are less likely to breastfeed (77% vs 86%) and those who do continue for a shorter duration (12 vs 17 weeks) (Hummel 2007). Fasting blood sugars are lower during exclusive breastfeeding. Milk production may be limited with unstable insulin levels. There is a period of hypoglycaemia after delivery following which Insulin requirements may be reduced by 27% (Davies 1989), In another study (Whichelow 1983) diabetic mothers increased their carbohydrate intake by 50g whilst breastfeeding whilst requiring 40 units insulin compared with 45 units pre-pregnancy. Immediately after delivery carbohydrate snacks should be available and glucose tablets to counteract any hypoglycaemia. Mothers should be reminded to have snacks available during night-time feeds and to monitor blood glucose levels if necessary, in order to adjust insulin requirements

Alves (2012) studied 123 children with type 1 diabetes and their siblings as case controls. Whilst there was no difference between breastfeeding, those children with type 1 diabetes were breastfed for a shorter time (3.3 vs 4.6 months) and were exposed to cow’s milk earlier than their siblings.

Mothers with diabetes are at risk of developing pre-eclampsia and should take 75 mg aspirin daily from 12 weeks’ pregnancy until delivery. Infants born to diabetic mothers have a 25–40% incidence of hypoglycaemia in the first one to two hours after delivery (Chertok 2009). This is transient and resolves spontaneously. Mothers with diabetes may have delayed lactogenesis II. Perez-Bravo et al. (1996) suggested that the risk of a child developing diabetes is 13 times higher if a susceptible infant is exposed to cow’s milk protein in the first three–four hours after delivery. The DAME (Diabetes and Antenatal Milk Expressing 2017) study provided evidence that providing the baby with previously expressed and stored colostrum rather than infant formula or oral glucose did not increase the risk of admission to NICU and is therefore preferable. This is also true for mothers with gestational diabetes or type 2 diabetes managed by insulin in pregnancy.

Treatment

Insulin is safe for use by breastfeeding mothers as the molecule is too large to pass into breastmilk (molecular weight > 6000). It has no hypoglycaemic effect from oral absorption as it is inactivated in the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, it would not be expected to exert any action on the infant’s glycaemic control. Breastfeeding may lower a woman’s insulin requirements by up to 30%. To prevent hypoglycaemic attacks, mothers may need to increase their carbohydrate intake or decrease their insulin dose.

During pregnancy and breastfeeding, insulin requirements may be altered, and doses should be assessed frequently by an experienced diabetes physician as well as by regular monitoring. The dose of insulin generally needs to be increased in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy.

References

- Alves JG, Figueiroa JN, Meneses J, Alves GV. Breastfeeding protects against type 1 diabetes mellitus: a case-sibling study. Breastfeed Med. 2012 Feb;7(1):25-8

- Chertok IRA, Raz I, Shoham I et al Effects of early breastfeeding on neonatal glucose levels of term infants born to women with gestational diabetes. J Hum Nutr Diet 2009;22(2): 166-9

- Davies RR, McEwen J, Moreland TA, Durnin C, Newton RW. Improvement in morning hyperglycaemia with basal human ultratard and prandial human actrapid insulin–a comparison of injection regimens. Diabetic Medicine 1988; 5:671-5.

- Foster, DA, et al (2017), Advising women with diabetes in pregnancy to express breastmilk in late pregnancy (Diabetes and Antenatal Milk Expressing [DAME]): a multicentre, unblinded, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31373-9

- Pérez-Bravo F, Carrasco E, Gutierrez-López MD, Martínez MT, López G, García de los Rios M, Genetic predisposition and environmental factors leading to the development of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in Chilean children, J Mol Med, 1996;74(2):105–9.

- S. Hummel C. Winkler S. Schoen A. Knopff S. Marienfeld E. Bonifacio A. G. Ziegler. Breastfeeding habits in families with Type 1 diabetes. Diabetic Med. 2007; 24 (6): 671-676

- Whichelow MJ, Doddridge MC. Lactation in diabetic women. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;3;287(6393):649–650.

Type 2 Diabetes and Breastfeeding

Information taken from Breastfeeding and Chronic Medical Conditions available from Amazon

Type 2 diabetes develops over weeks and months rather than suddenly as type 1 diabetes does. It is estimated that 415 million people across the world are living with diabetes, approximately 1 in 11 of the world’s adult population. Type 2 diabetes is now becoming far more common in children and in young people. The number of people of any age with type 2 diabetes is increasing in the UK, as it is more common in people who are overweight or obese. It also tends to run in families. It is around five times more common in South Asian and African-Caribbean people (often developing before the age of 40 in this group). It is estimated that there are around 750,000 people in the UK with type 2 diabetes who have not yet been diagnosed with the condition.

Gunderson (2018) showed that increasing lactation duration was associated with a strong, graded relative reduction in the incidence of type-2 diabetes even after accounting for pre-pregnancy biochemical measures, clinical and demographic risk factors, gestational diabetes, lifestyle behaviours, and weight gain. The graded risk reduction ranged from 25% for 6 months or less to 47% for 6 or more months of lactation. Shwarz (2009) had previously demonstrated that women who reported a lifetime history of more than 12 months of lactation were 10-15% less likely to have hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, and cardiovascular disease than those who had not breastfed. Breastfeeding could be said to be a positive health intervention based on these results.

Type 2 diabetes has symptoms like excessive thirst (often drinking considerable amounts of fruit squashes), needing to pass urine frequently and tiredness particularly after meals. Early symptoms of high glucose levels can be reversed by diet and exercise. At any stage lifestyle interventions can prevent further development and reverse the diagnosis.

Risk factors for type 2 diabetes are:

- Having a first-degree relative with type 2 diabetes.

- Being overweight or obese.

- Having a waist measuring more than 31.5 inches (80 cm) if you are a woman or more than 37 inches (94 cm) if you are a man. Central obesity occurs because of the effect of insulin pushing excess sugar into abdominal fat cells over the years.

- Having impaired glucose tolerance.

- Having gestational diabetes

Treatment

Non-insulin dependent diabetes (type 2 diabetes) treatment can be commenced with metformin, if dietary modification alone has not produced glycaemic control. There were no reported adverse effects on the babies in the published studies including effect on baby’s blood sugar.There is no data on any of the other oral drugs used to treat diabetes which should therefore be avoided. If metformin does not achieve control of blood sugars a breastfeeding mother may need to initiate insulin for the duration of her lactation.

Sulfonylureas be avoided during breastfeeding as they may produce hypoglycaemia in breastfed infant; Glibenclamide, Gliclazide, Glimepiride, Glipizide, Tolbutamide

There is no data on any of the other oral drugs used to treat diabetes which should therefore be avoided. If metformin does not achieve control of blood sugars a breastfeeding mother may need to initiate insulin for the duration of her lactation.

Dipeptidyl peptidase – 4 – inhibitors (Gliptins): Alogliptin, Linagliptin, Saxagliptin, Vildagliptin

Glucagon-like peptide1 receptor agonists: Albiglutide, Dulaglutide, Exanatide, Liraglutide, Lixisenatide

Meglitinides: Nateglinide, Repaglinide

Thioglitazones: Pioglitazone

References

- Gunderson EP, Hurston SR, Ning X, Lo JC, Crites Y, Walton D, Dewey KG, Azevedo RA, Young S, Fox G, Elmasian CC, Salvador N, Lum M, Sternfeld B, Quesenberry CP Jr; Study of Women, Infant Feeding and Type 2 Diabetes After GDM Pregnancy Investigators. Lactation and Progression to Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus After Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Dec 15;163(12):889-98)

- Schwarz EB, Brown JS, Creasman JM, et al. Lactation and maternal risk of type 2 diabetes: a population-based study [published correction appears in Am J Med. 2011 Oct;124(10): e9]. Am J Med. 2010;123(9):863.

Gestational diabetes and breastfeeding

Information taken from Breastfeeding and Chronic Medical Conditions available on Amazon.

Gestational Diabetes is described as impaired glucose tolerance in pregnancy. It is also increasing in prevalence due to obesity rates and now affects some 7% of pregnancies. Most women will need oral metformin to reduce blood glucose or insulin if changes in diet and exercise do not control gestational diabetes effectively. Risk factors for gestational diabetes are.

• BMI above 30 kg/m2

• previous macrosomic baby weighing 4.5 kg or above

• previous gestational diabetes

• family history of diabetes (first‑degree relative with diabetes

• minority ethnic family origin with a high prevalence of diabetes.

Kjos (1993) recommended that delivery should be contemplated at 38 weeks and, if not pursued, careful monitoring of foetal growth should be performed to reduce the risk of large for gestational age babies and shoulder dystocia.

Medication is normally discontinued after delivery although a proportion of mothers will go on to develop Type 2 diabetes. Women with gestational diabetes who do not breastfeed are twice as likely to develop future diabetes (Kjos 1993).

Gunderson (2012) studied 522 women diagnosed with gestational diabetes 6-9 weeks after delivery. Exclusive or mostly breastfeeding was associated with improved fasting glucose and lower insulin levels at this time. Lactation was seen to have favourable effects on glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity that may reduce the risk of diabetes after delivery. These findings continued for 2 years after delivery (Gunderson 2015).

Infants born to diabetic mothers have a 25-40% incidence of hypoglycaemia in the first one to two hours after delivery. This is transient and resolves spontaneously. Mothers with diabetes have delayed lactogenesis 2. This raises the risk if babies being supplemented which as Perez-Bravo reported increases the risk of future diabetes for the baby. To reduce the risk, it has become increasingly common to suggest that mothers express and store colostrum from 36 weeks gestation. The DAME trial studied 635 women with diabetes. The primary outcome of the trial was the proportion of infants admitted to the NICU post-natally. The results showed that there was no difference between groups (antenatal expression or normal care). They concluded that there was no harm in encouraging antenatal expression of colostrum twice a day in mothers with uncomplicated pregnancies.

References

- Brown A. Jones W A guide to supporting breastfeeding for professionals. Routledge 2019

- Davies HA, Clark J. D., Dalton K. J., and Edwards O. M. Insulin requirements of diabetic women who breast feed. BMJ. 1989 May 20; 298(6684): 1357–1358.

- Forster, D A, Moorhead AM, Jacobs SE, , Davis PG, Walker SP, McEgan KM, Opie GF, Donath SM, Gold L, McNamara C, Aylward A, East C, Ford R, Amir LH, Advising women with diabetes in pregnancy to express breastmilk in late pregnancy (Diabetes and Antenatal Milk Expressing [DAME]): a multicentre, unblinded, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2017;389: 2204 – 2213

- Gunderson EP, Hedderson MM, Chiang V, Crites Y, Walton D, Azevedo RA, Fox G, Elmasian C, Young S, Salvador N, Lum M, Quesenberry CP, Lo JC, Sternfeld B, Ferrara A, Selby JV. Lactation intensity and postpartum maternal glucose tolerance and insulin resistance in women with recent GDM: the SWIFT cohort. Diabetes Care. 2012 Jan;35(1):50-6.

- Hummel S Winkler C, Schoen S, Knopff A, Marienfeld S, Bonifacio E, Ziegler AG. Breastfeeding habits in families with Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2007 Jun;24(6):671-6

- Jones W Breastfeeding and Medication 2nd Ed 2018 Routledge UK

- Kjos SL, Henry OA, Montoro M, Buchanan TA, Mestman JH. Insulin-requiring diabetes in pregnancy: a randomized trial of active induction of labour and expectant management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993 Sep;169(3):611-5.

- Liu B, Jorm L, Banks E Parity, breastfeeding, and the subsequent risk of maternal type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2010; 33(6): 1239-41.

- Milne N Managing diabetes in women during preconception and pregnancy Clinical Pharmacist 2017; 9 (9)

- NICE Diabetes in pregnancy: management from preconception to the postnatal period NG3

- NICE Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management CG107

- Pérez-Bravo F. Carrasco E Gutierrez-López M. D. Martínez M. T. López G. García de los Rios M. Genetic predisposition and environmental factors leading to the development of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in Chilean children Journal of Molecular Medicine 1996;74(2):105-109

- Whichelow MJ, Doddridge MC. Lactation in diabetic women. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983; 3;287(6393):649–650).

Accidental dose of codeine when breastfeeding

Interestingly I am getting more reports of mums who have taken codeine accidentally – having opened the wrong packet, or been given it by supportive partners or relatives and friends. They are terrified that they have to stop breastfeeding and ask for how long they need to pump and dump their milk (such a terrible risk of liquid gold!). Here is the answer!

Accidental codeine / one dose and breastfeeding factsheet

Codeine is no longer recommended for breastfeeding mothers following recommendations by MHRA in 2016 . However, it seems that many women are prescribed codeine by GPs or discharged with it from secondary care with instructions not to breastfeed the baby. Until the baby in Canada died (ref) we routinely used co-codamol for all post-natal mothers.

Not everyone has the metabolism which concentrates the drug and its metabolites into milk. For them the drug is effective and neither they nor their babies exhibit side effects. For others, including my own family, codeine makes us feel sick and dizzy. It also seems to cause drowsiness in my breastfed grandchildren so that they sleep longer and more frequently if their mothers take it.

Accidental consumption of a single dose of codeine by a lactating mother need not lead to expressing and discarding of her breastmilk if her baby is term, fit and well. She should observe the baby for signs of drowsiness and if that happens make sure the co-codamol is kept out of the way in the future. But no need to panic and no need to stop breastfeeding for a single dose unless the baby develops breathing problems.

In answer to the queries it takes 15 hours for all the codeine to be removed from the body including milk.

Oral Terbinafine and breastfeeding

Some mothers develop fungal nail infections in pregnancy and delay treatment. When breastfeeding, topical treatments are preferable. I am asked at least once a week about oral terbinafine – hard to answer with little research. Hope this information helps with shared decision making.

Oral terbinafine and breastfeeding factsheet

Oral Terbinafine is sometimes used to treat fungal infection of the nails if topical products have failed to resolve symptoms. Treatment generally lasts for 3 months.

The most frequent adverse effects (for the mother) after oral use of terbinafine hydrochloride are gastrointestinal disturbances such as nausea, diarrhoea and mild abdominal pain. Loss or disturbance of taste may occur and occasionally may be severe enough to lead to anorexia and weight loss. Terbinafine hydrochloride is well absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. The bioavailability is about 80% because of first-pass hepatic metabolism. Some people are unable to tolerate the drug because of side effects.

Oral terbinafine is extensively bound to plasma proteins (99%) so passage into breastmilk might be expected to be low. The only research refers to two women given a single dose of 500 mg; the total level of terbinafine measured in breastmilk during the 72-hour post-dosing period was 0.65 mg in one mother and 0.15 mg in another. Neither woman was breastfeeding, but both were producing some breastmilk (218 ml and 41 ml, respectively). After 18 hours, the levels of terbinafine were below the level of detection.

The volume of milk being produced by the mothers makes this study questionable as an evidence base. Similarly, the single dose does not replicate normal treatment. However, the authors suggested that using the average milk concentration values over the 24-hour period in the two subjects, an exclusively breastfed infant would receive 3.8% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage of terbinafine.

Although unlicensed terbinafine has been used to treat tinea capitis in children (Gupta et al. 2003).

Skin concentrations may be up to 75-fold higher than those in the blood. It may persist in the skin for up to 8 weeks after the drug has been discontinued and in the nails for up to a year although treatment is stopped much sooner

The BNF reports that manufacturer advises avoidance of cream or tablets as it is present in milk but less than 5% of the dose is absorbed after topical application of terbinafine.

References

• Leachman SA, Reed BR, The use of dermatologic drugs in pregnancy and lactation, Dermatol Clin, 2006;24:167–97.

• Gupta AK, Adamiak A, Cooper EA, The efficacy and safety of terbinafine in children, J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2003;17:627–40.

• Thieme G, Peuckert U, Report on a pharmacokinetic study of SF 86-327 in healthy females in the ablactation period. Sandoz document number 303-019. 1986 (information taken from report in Lactmed and Hale 2017 online access).

Further information

• www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/2019/october/superficial-fungal-infections

• https://dermnetnz.org/topics/terbinafine/

See also

https://www.e-lactancia.org/breastfeeding/terbinafine/product/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501397/

Limited information indicates that oral maternal doses of 500 mg daily produce low levels in milk and would not be expected to cause any adverse effects in breastfed infants, especially if the infant is older than 2 months. Monitor the infant for jaundice or other signs of liver toxicity, especially in younger, exclusively breastfed infants

email wendy@breastfeeding-and-medication.co.uk